Forced Migration and Hunger

The 2018 Global Hunger Index (GHI) report—the thirteenth in an annual series—presents a multidimensional measure of global, regional and national hunger. The latest data available shows that while the world has made progress in reducing hunger since 2000, we still have a long way to go. Approximately 124 million people suffer acute hunger, a striking increase from 80 million two years ago. Levels of hunger are still serious or alarming in 51 countries and extremely alarming in one country, with the current trajectory leading to 50 countries failing to achieve low hunger by 2030.

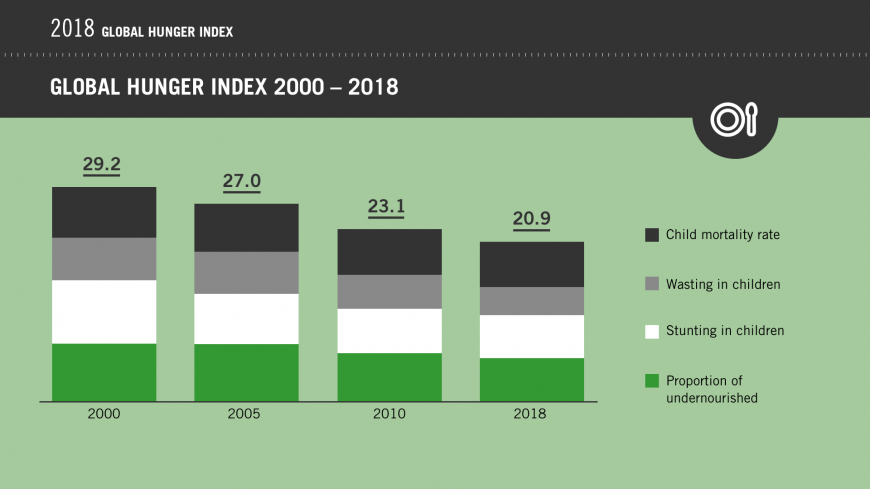

However, there is cause for optimism. The level of hunger worldwide has been reduced from 29.2 points in 2000 to 20.9 points in 2018; a 28% decrease. Overall trends are promising and show improvements over time with 27 countries within this year’s GHI having moderate levels of hunger and 40 countries having low levels of hunger. In addition, countries which have experienced conflict and wars in the past, resulting in extremely alarming levels of hunger, have seen significant reductions in hunger once their situations have stabilized.

Overall, despite areas of improvement, this year’s Global Hunger Index reveals a distressing gap between the current rate of progress in the fight against hunger and undernutrition and the rate of progress needed to eliminate hunger. This report highlights the parts of the world where achieving this goal will be the most challenging and where acceleration in the reduction of hunger is most critical. For these areas, this much-needed acceleration will require not just diligence in implementing the plans and policies that are currently in place, but increased efforts, innovative thinking and a commitment to working more deeply and broadly to address the root causes of hunger.

The 2018 edition has a special focus on the theme of forced migration and hunger. It features an essay by Laura Hammond of SOAS University of London, in which Hammond analyses the interplay between the two. She argues that hunger can be both a cause and a consequence of the vast movement of displaced populations, but states that links are often poorly understood and misperceived.

What should we take from the GHI 2018? How is ACTED contributing to progress?

Progress has been made in reducing hunger, but it has been too slow and hard-won gains are now being threatened

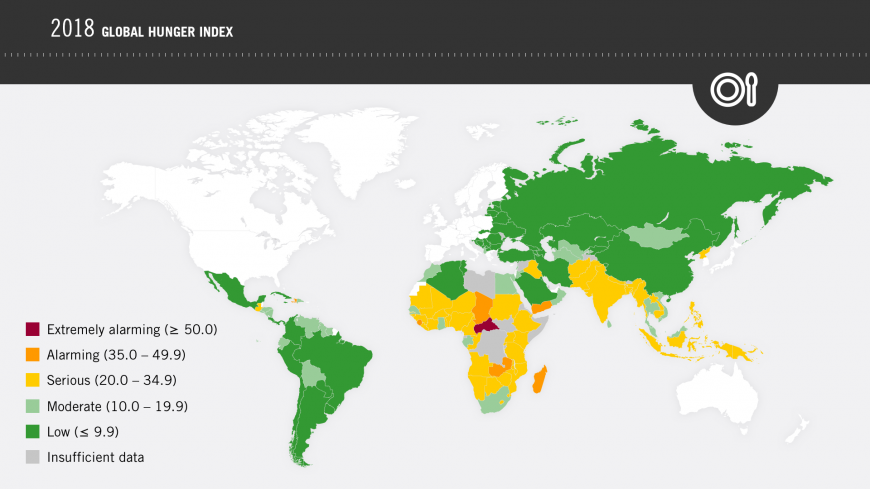

If progress in reducing hunger and undernutrition continues its current trajectory, an estimated 50 countries will fail to achieve low hunger by 2030, as measured by the GHI. At present, 79 countries have moderate to extremely alarming levels of hunger according to the 2018 GHI.

The GHI also reports that the level of hunger and malnutrition worldwide has been reduced from 29.2 points in 2000 to 20.9 points, representing a decline of 28% in this period. Underlying this improvement are reductions in each of the four GHI indicators: the prevalence of undernourishment, child stunting, child wasting and the mortality rate of children under age 5.

Six countries suffer from levels of hunger that are alarming: Chad, Madagascar, Sierra Leone, Zambia, Haiti and Yemen, while one country, CAR suffers from a level that is extremely alarming. 45 countries out of 119 countries that were ranked have serious levels of hunger.

→ ACTED’s work in CAR distributing agricultural inputs, training communities in agricultural techniques and supporting and promoting the development of livestock systems and agro-pastoral areas, all aim to combat this extremely alarming level.

→ ACTEDs interventions in Chad, Haiti and Yemen focus on the largescale food insecurity within these countries.

While progress has been strong in some parts of the world, in other parts hunger and undernutrition persist or have even worsened. Since 2010, 16 countries have seen no change or an increase in their GHI levels, including the Central African Republic (CAR), Madagascar and Yemen.

Hunger is a persistent threat to the lives of large numbers of forcibly displaced people

Across the globe, almost 70 million people are currently forcibly displaced, the highest number since records began. They are compelled to flee conflict, violence and natural or human-made disasters. Most people are displaced not as the result of just one factor, but because of a combination of factors with hunger often figuring prominently in their experience.

Many of the countries with the highest incidence of hunger in the 2018 GHI are also places affected by conflict, political violence and population displacement, with hunger often a cause and a consequence of displacement.

→ ACTED’s work in places of increased violence and conflict such as Nigeria, Somalia, South Sudan and Yemen all involve large interventions related to improving food security and combatting malnutrition.

In Burundi, DRC, Eritrea, Libya, Somalia, South Sudan and Syria — seven countries where no GHI scores could calculated — hunger is a cause for significant concern. Violent conflict, political unrest and/or extreme poverty have caused substantial flows of forced migration, which is closely associated with food insecurity.

More needs to be done to address the causes of forced migration and hunger and provide long-term solutions for displaced people and their host communities

Since most forced migration is often lasting years or generations, long-term solutions for displaced people – including income-generation opportunities, education and training—are vital.

→ ACTED’s commitment to promoting inclusive and sustainable growth takes on this longer-term perspective, focusing on productive employment as a means of increasing incomes of poor and displaced people and, as a result, raising their standards of living.

People facing food insecurity tend to seek the closest possible place of safety. As a result, 85 per cent of all displaced people are hosted in low- and middle-income countries. Since the vast majority of food-insecure displaced people stay in their region of origin, support should be focused in these areas.

Natural disasters like droughts, floods and severe weather events lead to hunger and substantial displacement only when governments are unprepared or unwilling to respond. This often occurs either because governments lack the capacity to respond, or because they engage in deliberate neglect or abuse of power.

Support is needed for policies designed to prevent conflict and build peace, as well as for policies that reinforce government accountability and transparency. These values make it more difficult for governments to shirk their duty to meet citizens’ basic needs for safety and food security.

→Under ACTED’s pillar of co-constructing effective governance, we aim to fight global hunger through by supporting an empowered, pluralistic civil society, social cohesion and effective and responsive public institutions.

Many host communities face a disproportionate burden. As displacement can bring food insecurity to host populations, stronger support for host communities is crucial.

What are the key recommendations?

Implement Long-Term Solutions

• Link humanitarian assistance with development cooperation to strengthen the resilience of displaced populations, supporting displaced people’s access to education and training, employment, healthcare, agricultural land and markets to increase self-reliance

• Implement durable solutions, such as local integration or return to regions of origin on a voluntary basis, in addition to expanding safe, legal pathways for refugees through resettlement schemes, such as humanitarian admission programs

• Support flexible approaches that allow people to maintain businesses, livelihoods and social ties in multiple locations

• Design policies and programs that recognize the complex interplay between hunger and forced migration as well as the dynamics of displacement

Leave No One Behind

• Focus strong and sustained support and attention on the regions of the world where most displaced people are located, i.e. low- and middle-income countries and the least-developed countries

• Provide stronger political and humanitarian support to internally displaced people (IDPs) and advocate for their legal protection

• Follow up on UN Resolution 2417 (2018), which focuses on the links between armed conflict, conflict-induced food insecurity and the threat of famine

• Prioritize the special vulnerabilities and challenges of women and girls, ensuring that displaced women and girls have equal access to assets, services, productive and financial resources and income-generating opportunities

• Scale up investment and improve governance to accelerate development in rural areas, supporting people’s efforts to diversify their livelihoods and secure access to land, markets and services

Show Solidarity, Share Responsibility

• Countries should address the root causes of forced displacement by funding, implementing and reporting on their commitments under Agenda2030, especially in the areas of poverty and hunger reduction; climate action; responsible consumption and production; and promotion of peace, justice, and strong institutions

• Foster a fact-based discussion around migration, displacement and refugees. Governments, politicians, international organizations, civil society and the media should work to proactively counter misconceptions and promote a more informed debate on these issues.

• Adopt and implement the UN Global Compact on Refugees (GCR) and the Global Compact for Safe, Orderly and Regular Migration (GCM), and integrate their commitments into national policy plans

• Governments should deliver on and scale up their commitments to international humanitarian organizations that support refugees and IDPs and close the funding gaps that already exist.

• Uphold humanitarian principles and human rights when assisting and hosting refugees, IDPs and their host communities. Do not use official development assistance as a bargaining chip in negotiations over migration policies.

What is the Global Hunger Index?

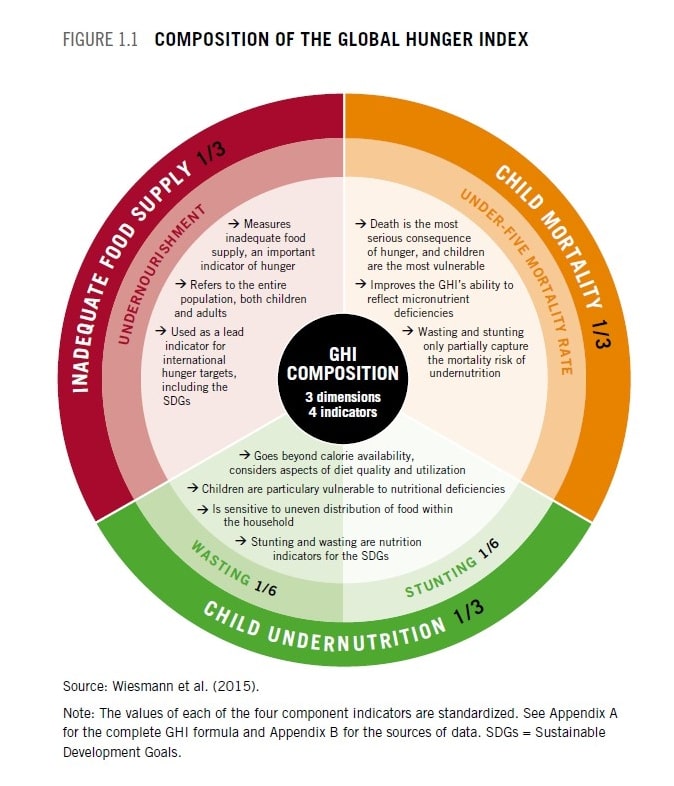

The GHI scores are based on a formula that captures three dimensions of hunger—insufficient caloric intake, child undernutrition and child mortality—using four indicators:

• UNDERNOURISHMENT: the share of the population that is undernourished, reflecting insufficient caloric intake

• CHILD WASTING: the share of children under the age of five who are wasted (low weight-for-height), reflecting acute undernutrition

• CHILD STUNTING: the share of children under the age of five who are stunted (low height-for-age), reflecting chronic undernutrition

• CHILD MORTALITY: the mortality rate of children under the age of five

Data on these indicators come from the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO), the World Health Organization (WHO), UNICEF, the World Bank, Demographic and Health Surveys (DHS) and the United Nations Inter-agency Group for Child Mortality Estimation (UN IGME). The 2018 GHI is calculated for 119 countries for which data are available and reflects data from 2013 to 2017.

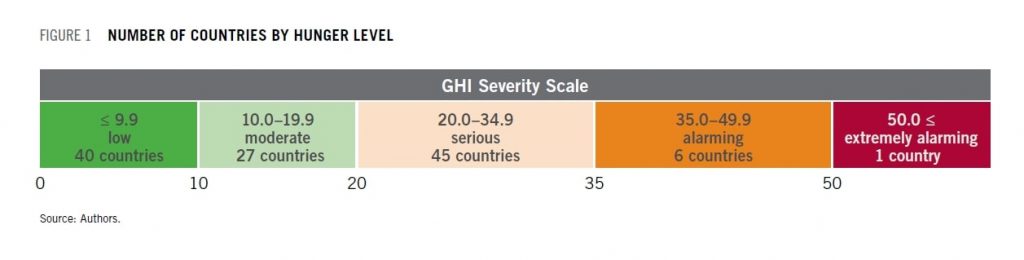

The GHI ranks countries on a 100-point scale, with 0 being the best score (no hunger) and 100 being the worst, although neither of these extremes is reached in actuality. Values less than 10.0 reflect low hunger; values from 10.0 to 19.9 reflect moderate hunger; values from 20.0 to 34.9 indicate serious hunger; values from 35.0 to, and 49.9 are alarming; and values of 50.0 or more are extremely alarming (Figure 1).